The challenge that delegated legislation poses to parliamentary sovereignty and associated supremacy in the UK is purportedly addressed through what we term the ‘constitutional bargain of delegated law-making’. This has three elements: the proper limitation of delegation by Parliament through well-designed parent legislation; the exercise of self-restraint by the Executive in the use of delegated authority; and the enablement of meaningful scrutiny by Parliament. As a paradigm situation in which delegated law-making might be said to be necessary, the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic is an apposite context in which to assess the robustness of that bargain. Our analysis uses a sample of Westminster-generated pandemic-related secondary instruments as a peephole into the broader dynamics of this constitutional bargain and further reveals its significant frailties; frailties that are exposed, but not created, by the pandemic.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution and reproduction, provided the original article is properly cited.

Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Society of Legal Scholars

Delegated legislation has caused constitutional anxiety for decades. Even while conceding its indispensability to effective governance, Footnote 1 particularly in situations requiring rapid or highly technical responses, scholars, parliamentarians, and courts have long accepted that delegated legislation is a deviation from the alleged paradigm mode of law-making in parliamentary democracies: primary legislation. Footnote 2 In the United Kingdom (UK), the challenge that delegated legislation poses to the cardinal principle of parliamentary sovereignty and associated supremacy has been purportedly answered through what we term the ‘constitutional bargain of delegated law-making’. Building on parliamentary committees’ long-standing observations, we claim that this has three elements: the proper limitation of delegation by Parliament through well-designed parent legislation; the exercise of self-restraint by the Executive in the use of delegated authority; and the enablement of meaningful scrutiny by Parliament. Footnote 3 The Covid-19 pandemic offers a critical context in which to explore how this constitutional bargain reveals its limits when confronted by the stresses of extensive delegated law-making.

Legislation has been an important part of the UK government's response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Footnote 4 While the Coronavirus Act 2020 (CVA 2020) was the flagship pandemic primary legislation passed specifically in response to coronavirus, introduced at speed and conferring extensive powers on Government, Footnote 5 the majority of pandemic law-making has been delegated. One might claim that this is unremarkable: the pandemic required swift and sometimes emergency action, often on highly technical matters, in a rapidly changing social and epidemiological context wherein some flexibility was reasonably required. In other words, the pandemic at least initially seemed to present many of the classically recognised conditions in which delegating law-making might be said to be necessary, Footnote 6 and parliamentarians seemed in broad agreement that an urgent legislative response enabling delegation was required and appropriate. Footnote 7 However, as time passed and the pandemic persisted, so too did the reliance on delegated legislation, leading to widespread concern. Footnote 8 We note that between March 2020 and May 2022, the Government laid over 580 Covid-19-related statutory instruments before Parliament, Footnote 9 and there is persistent concern that the Government's reliance on delegated law-making is part of a wider trend of executive dominance posing a fundamental threat to parliamentary democracy. Footnote 10

This paper contributes to this growing literature by using a sample of Covid-19 regulations as a context in which to pursue an empirically informed analysis of whether, in the context of Westminster, the constitutional bargain of delegated law-making held up during the first year of the pandemic. Footnote 11 In doing so, we do not wish overly to exceptionalise the Covid-19 pandemic as a period of especially unusual law-making. We are conscious that pandemic law-making has taken place against the backdrop of extensive delegated law-making related to Brexit, Footnote 12 as well as a growing practice of conferring wide-ranging delegated powers in primary legislation. However, we consider that as a paradigm situation in which delegated law-making might be said to be necessary, the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic is an apposite context in which to assess the robustness of that bargain. We are also conscious that concerns about the use of delegated or executive law-making during the pandemic are not unique to the UK. Footnote 13 Although our study focuses on the Westminster Parliament, and our analysis is grounded in the longstanding debates about delegation that relate specifically to this context, the broader concern – with parliamentary marginalisation – has wider resonance.

Our analysis uses a sample of the secondary instruments applying to England and introduced by the UK Government as part of the pandemic response as a lens into broader dynamics. Footnote 14 The sample comprises 81 Covid-related regulations, a list of which is set out in full below in the Appendix. They were chosen on the basis that these were the regulations that were subject to Parliamentary debate over the first year of the pandemic, ie between March 2020 and March 2021. 330 other Covid-19 regulations also passed that year were subject to the negative procedure and not debated in Parliament. The total of 415 Covid-related regulations passed that year formed approximately a third of the total 1,206 statutory instruments made during that 12-month period. Footnote 15

The regulations were identified using the Hansard search engine. We used the search engine to find all debates concerning ‘coronavirus regulations’ listed between 9 March 2020 and 9 March 2021. This generated 123 results. These results were then filtered down to determine the number of regulations that were subject to substantive debates, as listed in the Appendix. This required us to identify which regulations had been debated, and how many times (as some regulations were subject to more than one debate, having been debated in both Houses of Parliament, or both a House and the Delegated Legislation Committee). Notably, there were challenges in doing this. First, some regulations were referred to in slightly different ways in Hansard – ie in most cases the House of Lords referred to draft regulations without using the word ‘draft’ in the debate title, but on examining the debate it was clear that the regulations were in fact draft regulations. Secondly, a challenge arose in identifying whether regulations listed for debate on the same day were debated or not. While some appeared to have been debated and then approved, and others to have been approved without debate, closer reading of the debates on regulations that took place on the relevant day led us to identify what we term bundle and umbrella debates in the Appendix. Bundle debates occurred when a debate listed as being on one set of regulations actually expanded to and covered the contents of other regulations that were voted on later that day. This usually arose where the Minister sponsoring the regulations explicitly referred to those other regulations in their contributions. Umbrella debates occurred when the debate on one set of regulations covered a topic that was closely related with the title and contents of a set of regulations that was voted later that day. For instance, on 12 October 2020 three sets of regulations on mask-wearing were listed for debate at the Lords but the record seems to suggest that only the first one was debated. Although we found no explicit reference to the other two regulations, the content and context of the debate led us to conclude that it covered all of them. We refer to these as ‘umbrella debates’ and list the regulations approved following them. Finally, there was one debate listed on prospective (rather than draft) regulations concerning assisted dying. This was nonetheless included in the Appendix.

In carrying out our analysis, we assessed several general features of the 81 regulations. These included whether and when they were in force, whether they were debated by themselves or alongside other regulations, in what part or parts of Parliament they were debated, and what parent Act they were passed under. This revealed that 75 of the 81 regulations we considered were already in force when they were debated and 10 were in draft form (ie not yet in force). These debates ordinarily considered only one regulation, although on certain occasions bundle and umbrella debates were held that concerned multiple regulations at the same time. Footnote 16 In the main, the debates took place in the House of Lords and the Delegated Legislation Committee. Footnote 17 On two occasions, there were debates on draft regulations in the House of Commons. This followed a government commitment to ‘consult’ Parliament on ‘significant measures’ in advance of their coming into force ‘wherever possible’. Footnote 18 The first of these debates enabled the House of Commons to scrutinise seven draft Covid-19 regulations on 13 October 2020. Footnote 19 The second debate considered the impact of proposed new coronavirus regulations on the ability of terminally-ill adults to travel abroad for an assisted death. Footnote 20 Our analysis relied on the record of all these debates in Hansard, totalling the equivalent of approximately 54 hours of parliamentary time.

Almost all the regulations contained in our sample were passed or proposed using powers contained in the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984 (PHA 1984) Footnote 21 (65 regulations, one draft regulation) with only a one regulation flowing from the CVA 2020 Footnote 22 (one draft regulation). That said, our sample does illustrate the wide array of parent Acts, some joint parent Acts, that have been used for Covid-related delegated law-making. The included regulations were also made under the Road Traffic Act 1988 (one regulation), the Vehicle Excise and Registration Act 1994 and the Road Traffic Act 1988 and the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (one regulation), the Energy Act 2013 (two regulations), the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 and the Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998 (two regulations), the Planning Act 2008 (one regulation), the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (one regulation), the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Act 2009 (one regulation), the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (three regulations), the Business and Planning Act 2020 (one regulation), the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (one regulation). One further set of proposed regulations was debated without the parent Act being identified at the time. Footnote 23

Our analysis of this sample reveals significant frailties across all three dimensions of the constitutional bargain. After having set out the nature and source of the constitutional bargain in delegated law-making in Part 1, we reveal in Part 2 three ways in which this bargain was undermined during the pandemic. The first is that by creating ‘skeleton Acts’ before and during the pandemic – giving Government wide latitude that was used for pandemic law-making – Parliament failed to appropriately delimit delegated law-making. The second is that the Executive failed to exercise self-restraint in the use of such delegated authority. The third is that Parliament was denied opportunities for meaningful scrutiny of these regulations.

These frailties expose a rupture of the delicate balance between delegation and abrogation that is foreseen as a means of managing the potential constitutionalist deficits of delegation and associated undermining of parliamentary sovereignty. As we outline in the conclusion, that bargain is not irredeemable: serious proposals exist that, if implemented, could shore up the constitutional bargain of delegated law-making and restore constitutional equilibrium.

As Jeff King has noted, it was the Donoughmore Committee, almost a hundred years ago, that developed a comprehensive understanding of the use of delegated law-making that set boundaries on its constitutionally appropriate use. Footnote 24 As we will show, these boundaries have been reinforced by subsequent Parliaments. Footnote 25 This understanding distinguished between ‘normal’ and ‘exceptional’ uses of delegated law-making, with the former being characterised by: (i) a clear delineation of powers; (ii) easy access to courts to enforce the vires of delegated legislation; (iii) transparency and easy accessibility of delegated legislation for citizens and public officials; and (iv) no conferral of powers to legislate on matters of principle, to raise taxes, or to amend or repeal primary legislation. For the Donoughmore Committee, exceptional uses of delegated law-making – using delegated legislation to legislate on matters of principle, creating Henry VIII powers, conferring ‘so wide a discretion on a Minister that it is almost impossible to know what limit Parliament did intend to impose’, or ousting judicial review – were constitutionally suspect. Footnote 26

Fundamental to the problématique of delegated legislation was the conferring of delegated law-making powers through ‘skeleton legislation’ that contained ‘only the barest general principles’ and permitted ‘matters which closely affect the rights and property of the subject [to] be left to be worked out in the Departments, with the result that laws are … [not] made by, and get little supervision from, Parliament’. Footnote 27

For the Donoughmore Committee, skeleton legislation of this kind was indicative of the deeper problems of ‘loosely defined powers’, Footnote 28 ‘inadequate scrutiny in Parliament’, Footnote 29 broad powers being used to ‘deprive the citizen of the protection of the Courts against action by the Executive which is harsh, or unreasonable’, Footnote 30 and a lack of transparency and publicity about the extent or existence of such powers. Quite understandably, given its practical utility, the Committee did not consider that such problems ‘destroy[ed] the case for delegated legislation’ but did argue that they showed the need for some safeguards to be put in place so that Parliament could ‘continue to enjoy the advantages of the practice without suffering from its inherent dangers’. Footnote 31

The problems identified by the Donoughmore Committee have not abated. Indeed, they have become more acute in the ninety years since its report was published. Continuing a trend that has been of concern for decades, Footnote 32 a huge amount of delegated legislation continues to be made, Footnote 33 Henry VIII powers are increasingly widespread, Footnote 34 and delegated law-making is heavily relied on to address complex but constitutionally significant ‘events’ like Brexit, Footnote 35 as well as issues with clear human rights and rule of law implications like deportation and asylum-related procedures, Footnote 36 and changes to criminal law. Footnote 37 There is an argument, then, that the ‘exceptional’ has become increasingly normalised; that secondary legislation is now routinely being used for purposes and in respect of issues that the Donoughmore Committee recognised as being ill-suited to delegation. At the same time, it is not at all clear that the safeguards the Donoughmore Committee called for operate effectively to maintain constitutional integrity in the light of this extensive use of delegated law-making. Footnote 38

We argue that these safeguards can be found in a three-part constitutional bargain on delegated law-making between the Executive and Parliament, comprised of proper limitation of delegation by Parliament, self-restraint on the part of the Executive, and meaningful scrutiny by Parliament. This way of conceptualising how to manage the long-standing tension between practicality and principle when it comes to delegated law-making clearly involves trade-offs. Robust limitation of delegation by Parliament may slow down policy responses by requiring more primary legislation to be passed before regulations can be produced. Meaningful parliamentary scrutiny may mean that regulations cannot immediately come into force. Executive self-restraint may limit policy, flexibility, dynamism, innovation or responsiveness. On the other hand, allowing delegation per se means that Parliament limits its capacity to influence and shape government action, making itself vulnerable to the extent of the Executive's commitment to self-restraint and accountability to Parliament. The constitutional bargain seeks not to resolve but to manage these tensions; to provide a framework to safeguard constitutional principle while enabling everyday governance.

Although overly broad parent legislation clearly runs the risk of giving excessive legislative power to the Executive and going beyond what is needed for technical or ‘merely’ regulatory purposes, there is no clear constitutional line indicating what is and what is not suitable for delegation. Instead, and in keeping with the principles of the UK constitution, parent Acts are treated – as all other acts are – as exercises in parliamentary sovereignty; expressions by Parliament of how much legislative power it wishes the Executive to enjoy. As in all situations of delegation, this produces a paradox: parent Acts at once express Parliament's sovereignty and undermine its role as the principal law-making body. Footnote 39 Seeking to manage this apparent paradox, parliamentary and special committees have developed the concept of ‘skeleton Bills’. Such Bills were first defined by the Donoughmore Committee as ones in which ‘only the barest general principles’ are outlined, which permit ‘matters which closely affect the rights and property of the subject [to] be left to be worked out in the Departments, with … little supervision from, Parliament’, Footnote 40 or which contain such significant delegated powers that the ‘real operation [of the Act] would be entirely by the regulations made under it’. Footnote 41 They have more recently been described by parliamentarians as broad delegated powers ‘sought in lieu of policy detail’. Footnote 42

As emphasised by the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC), primary legislation can be characterised as ‘skeleton’ either in toto or in respect of specific provisions. Footnote 43 In line with parliamentary committees and scholars, we take the view that skeleton provisions should be avoided wherever possible, and therefore that the scope of the powers should contain at least the gist of the policy so that Parliament is able to scrutinise its merits. In those exceptional circumstances where the government can put a convincing case for wide-ranging delegation, there is room for an alternative – if imperfect – approach whereby Parliament imposes concrete limitations. This approach gained some prominence in the context of the Brexit debate in regard to the domestication of EU law and the ministerial powers to correct deficiencies arising from withdrawal. Footnote 44 It does operate as a backstop, providing an opportunity to Parliament to firmly express that there are decisions that cannot be made without being subject to full legislative scrutiny, such as amending significant constitutional statutes, creating new criminal offences, or making retrospective legislation. Footnote 45 Either by preventing wide-ranging delegated powers clauses or by imposing substantive limits on the powers (no-go areas), Parliament is seeking to reinforce the bargain through such boundary-setting.

Several committees of Parliament operate to seek to identify and address potentially problematic proposed delegations during the legislative process. The separate Lords-only Committee – the DPRRC – considers proposed ministerial powers to make regulations contained in proposed primary legislation. The DPRRC then makes a report containing recommendations on these proposed powers, although this is usually made after a Bill has passed through the Commons and before the Lords’ Committee stage. Furthermore, other committees (notably the House of Lords Constitution Committee or, very rarely, the House of Commons Procedure Committee) may consider the implications of proposed delegations of law-making powers in particular Bills. Footnote 46 Once delegated powers provisions are in force, other committees scrutinise their exercise. The Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments (JCSI), whose membership is drawn from both Houses of Parliament, applies ‘technical scrutiny’ Footnote 47 of delegated legislation by assessing whether an instrument falls within the remit outlined in the parent Act. The JCSI can decide whether to draw the special attention of each House to any instrument on the grounds that, for example, the relevant parent Act immunises a delegated instrument from challenge before the courts, or that there ‘appears to be doubt about whether there is power to make it or that it appears to make an unusual or unexpected use of the power’. Footnote 48 The JCSI can also draw attention to delegated legislation on the basis that ‘there appears to have been unjustifiable delay in publishing it or laying it before Parliament’. Footnote 49 The Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee (SLSC) is another Lords-only Committee that assesses the policy merits of all secondary legislation. Footnote 50 There is also the Select Committee on Statutory Instruments (SCSI), comprised exclusively of MPs, which performs the same function as the JCSI. However, the SCSI considers secondary legislation which would not ordinarily be considered by the Lords, such as legislation relating to financial matters.

Notwithstanding this oversight of parent Acts, concern had been expressed prior to the pandemic that there was a ‘growing tendency for the Government to introduce “skeleton bills”, in which broad delegated powers are sought in lieu of policy detail’ Footnote 51 so that Parliament was ‘being asked to pass legislation without knowing how the powers conferred may be exercised by ministers and so without knowing what impact the legislation may have on members of the public affected by it’. Footnote 52 It is thus clear that this part of the constitutional bargain has been under strain for some time.

The corresponding part of the constitutional bargain is that in making delegated legislation the executive should exercise self-restraint and not go beyond the scope of the powers provided in the relevant parent Act. Footnote 53 We conceive this as encompassing both the formal principle of vires (ie that delegated legislation will be ‘held by a court to be invalid if it has an effect, or is made for a purpose, which is ultra vires, that is, outside the scope of the statutory power pursuant to which it was purportedly made’ Footnote 54 ), and a broader normative principle that, in order to respect parliamentary sovereignty, the Executive should exercise self-restraint in how it uses its delegated authority.

Such self-restraint comprises the Executive not stretching the limits of its delegated powers by using them to enact significant policy, or policy not directly or sufficiently relating to the description of powers given in the parent Act. Indeed, parliamentary committees have repeatedly stressed that significant policy change should not be enacted via delegated legislation even if doing so is strictly speaking intra vires. Footnote 55 For example, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution has stated ‘it is essential’ that ‘primary legislation is used to legislate for policy, and major objectives’ whereas delegated legislation must ‘only be used to fill in the details’. Footnote 56 It is clear that such restraint is a practical necessity in a context where the volume of delegated legislation passed every year is so high that the courts and Parliament combined are not capable of rigorous analysis of all such delegation. Moreover, some delegated powers currently in existence are very broad due to political circumstances, such as Brexit, in which the Government has claimed the need for flexibility. Footnote 57 In some circumstances, the only means by which the system can realistically function effectively is if the Government exercises its legislative capacity, but in a way that is respectful of Parliament's position as principal law-maker.

This element of the bargain is not fully dependent on the degree of commitment that a minister may have towards the principles of parliamentary accountability and democracy. Internal governmental legality checks can contribute to upholding constitutional principle. Thus, governmental lawyers will be involved in the drafting of a statutory instrument and will advise ministers on the lawful exercise of delegated powers. These lawyers, for instance, may advise on any Convention rights compatibility issues, on the requirements and expectations of the JCSI or the SLSC, or on whether a proposed exercise of delegated powers might be vulnerable to judicial review. Footnote 58 Recognising the limitations of the position of a civil servant whose ultimate role is to serve the government of the day, we submit that this interaction – and indeed potential tension – between the political and the bureaucratic components of the executive may result in some level of governmental self-restraint. Footnote 59 Nevertheless, strengthening this element of the bargain also depends on tightening existing guidance to express strong commitments towards constitutional principle. For instance, guidance indicates that a minister ‘should volunteer his or her view regarding [a statutory instrument's] compatibility with the Convention rights’. Footnote 60 While there is no equivalent legal requirement to the one imposed for the passage of Bills, Footnote 61 governmental commitment towards constitutional principle would be better served by clear and consistent practices of strengthening internal checks. Footnote 62

Thirdly, and finally, the constitutional bargain requires an internal procedural structure, which comes in the form of parliamentary scrutiny of the use of powers to make delegated legislation. Parliamentary committees play a significant role in subjecting delegated legislation to scrutiny. The general principle is that the more extensive and/or controversial the delegated legislation, the greater the scrutiny Parliament should subject it to. Footnote 63 However, in practice, it is the form rather than the substance of the delegated legislation that determines much about the kind of scrutiny a statutory instrument receives.

‘Draft affirmative instruments’ are laid in draft and cannot come into effect until they have been debated and approved by both Houses. ‘Negative instruments’ must be laid before Parliament for 40 days and can be rejected by a prayer motion. Footnote 64 ‘Made affirmative instruments’ come into force without approval of Parliament but require approval to remain in force beyond a period specified in the relevant parent Act (usually 28 or 40 sitting days). Footnote 65 The kind of delegated legislation used in any case will be determined by the parent Act, which may in some cases also lay down strengthened scrutiny procedures for specified instruments. Footnote 66

At least in principle, parliamentary scrutiny can ‘square the circle’ of the paradox of sovereignty/delegation and the inherent limitations of relying on institutional self-restraint by Government. However, it has long been clear that there are limits to such scrutiny as a means of maintaining the constitutional bargain, which have prompted calls for an overhaul of parliamentary scrutiny procedures. Footnote 67 These limits are both inherent and exogeneous.

The inherent limitations lie in the nature of parliamentary scrutiny itself, which as the SLSC has recently noted, is far less robust Footnote 68 than that afforded to primary legislation Footnote 69 in at least three ways: (i) delegated legislation is considered on an ‘all or nothing’ basis: it must be approved or disapproved in full and amendments are not possible; (ii) line by line scrutiny is not undertaken and delegated legislation is debated only once in each House; and relatedly (iii) rejection of a piece of delegated legislation is a ‘very rare occurrence’ Footnote 70 (and where it does happen can lead to ‘significant constitutional consequences’ Footnote 71 ).

Exogenous factors include the volume of delegated legislation (which by necessity reduces parliamentary capacity to subject it to robust scrutiny) and the extent to which governments enable rigorous scrutiny by, for example, encouraging and enabling prompt scrutiny and providing sufficient information to ensure that scrutiny is effective and meaningful. This is linked to two components of meaningful scrutiny for delegated law-making outlined by Tucker: public justification by the Government of the merits of the delegated legislation, and vulnerability of that legislation to defeat. Footnote 72 These two components clearly have the potential to shore up Parliament's role within delegated law-making and to ensure that delegation through primary legislation does not constitute a general licence to legislate without parliamentary engagement. However, as noted above, whether or not Parliament can actually undertake meaningful scrutiny is determined to a significant extent by the procedure used for secondary legislating. In this way, and as recently emphasised by David Judge, the proposition of effective parliamentary scrutiny assumes willingness by both Parliament to scrutinise and the Executive to be scrutinised. Footnote 73

Well before the Covid-19 pandemic, scholars, parliamentarians, and NGOs had expressed concern about the extent to which delegated law-making was being used to unbalance the constitutional order. However, the pandemic was precisely the kind of situation in which one might expect that delegated law-making would be appropriate for reasons of urgency, technical complexity, and the need to be responsive to changing circumstances. It was also a time during which one might have expected parliamentary anxieties to be heightened by the scale of the delegation, the intrusiveness of the measures introduced in response to the pandemic, and the human and material costs of the disease and its broader implications. However, as a moment of significant stress – indeed of emergency – the pandemic was also a context in which we might expect that strengths and weaknesses of existing systems might become visible. Indeed, that was the case in respect of delegated law-making in which, as we now turn to consider, the fraying edges of the constitutional bargain were exposed.

Our assessment of a sample of delegated legislation during the first year of the pandemic revealed that all three limbs of the constitutional bargain were undermined, as set out below. This is despite there being instances of good practice, particularly on the part of parliamentary committees and parliamentarians, in seeking to scrutinise delegated legislation.

The majority of delegated legislation drafted and enacted during the pandemic, and 65 of the 81 regulations we considered in our sample were made under the authority of Part 2A of the PHA 1984 which is properly understood as a skeleton provision. Footnote 74 Among other things, Part 2A provides a power to make regulations to prohibit events or gatherings, Footnote 75 to impose restrictions or requirements relating to dead bodies, Footnote 76 and to ‘impose or enable the imposition of restrictions or requirements on or in relation to persons, things or premises in the event of, or in response to, a threat to public health’. Footnote 77 These regulations may create criminal offences punishable by fines, permit or prohibit the levying of charges, confer functions on local authorities and other persons, and be imposed on the population as a whole, Footnote 78 although there are some requirements (for example, to submit to a medical examination) that cannot be imposed by such a regulation. Footnote 79 Clearly, these are extremely wide powers indeed; as the Court of Appeal put it in Dolan ‘[t]he words of [section 45C(1)] could not be broader’. Footnote 80 Within the parent Act, the only substantive restrictions are requirements that the measures would be ‘consider[ed]’ proportionate, and be ‘made in response to a serious and imminent threat to public health’. Footnote 81 Sections of the PHA 1984 are thus properly described and understood as skeleton provisions, so that the degree of latitude it provides to the Government is substantial.

Of course, there is an argument that this is appropriate; that the PHA 1984 rightly seeks not to be overly prescriptive because it was made in anticipation of a public health crisis, the exact nature of which could not have been foreseen. Indeed, Part 2A of the PHA 1984 was substantively introduced by amendment in 2008 and in anticipation of what the Court of Appeal has described as ‘a modern epidemic such as that caused by SARS’ Footnote 82 in the early 2000s. However, and importantly, these skeleton provisions on which the government did heavily rely do not seem to contain any real safeguards against the use of the authority delegated under them in situations where, in reality, Parliament was both ready and willing to take on a more proactive legislative role.

Part 2A of the PHA 1984 contains almost no limitations on ministerial power to make regulations under it; domestic regulations for health protection may only be made where the relevant minister ‘considers … that the restriction or requirement is proportionate to what is sought to be achieved by imposing it’, Footnote 83 and special restrictions or requirements may only be made if they are ‘in response to a serious and imminent threat to public health’ Footnote 84 or their imposition is made contingent on there being such a threat. Footnote 85 The first of these so-called restrictions adds nothing to what is now the general public law duty of proportionality or to the effects of the proportionality test as applied under the Human Rights Act 1998 Footnote 86 (both of which were established by 2008 when the relevant provisions were inserted into the PHA 1984), while the latter appears to have no significant limiting function as the triggering condition (the existence of ‘a serious and imminent threat to public health’) is the subject of a subjective judgement on the part of the relevant minister, albeit subject to judicial review for vires should proceedings challenging the lawfulness of any such regulations be taken. Notably, it seems likely that any such challenge would face considerable hurdles in seeking to establish a lack of vires given that, as the Court of Appeal put it, ‘the purpose of [Part 2A] clearly included giving the relevant Minister the ability to make an effective public health response to a widespread epidemic such as the one that SARS might have caused and which Covid-19 has now caused’. Footnote 87

Although just one of the regulations in our sample were made under the CVA 2020, this legislation, passed at great haste at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, is also properly understood as containing various skeleton provisions. As we have discussed elsewhere, parliamentarians were given just four days and 13 hours of debate time to consider the provisions in the CVA 2020, Footnote 88 yet it contains broad powers to create delegated legislation, including Henry VIII powers. Footnote 89 For example, it contains provisions for the Secretary of State to modify the Police Act 1997, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers (Scotland) Act 2000 and the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 to apply them to temporary commissioners and make consequential changes using the negative resolution procedure. Footnote 90 The CVA 2020 also created new powers to create delegated legislation through devolving powers of the kind contained in the PHA 1984 to Scotland and Northern Ireland. Footnote 91 Indeed, when the CVA 2020 was going through Parliament, the Shadow Health Secretary, Jonathan Ashworth MP, in stating that the Labour Party would reluctantly support the Act, described such powers as the ‘most draconian … ever seen in peacetime Britain’, and referred to the ‘huge potential for abuse’ of such powers ‘however well intended and needed’. Footnote 92 Moreover, as situation-specific (ie Covid-19 related only) legislation, the CVA 2020 does not contain tests of necessity and imminent threat such as those found in the PHA 1984. Rather, the safeguards are primarily in the form of (what we elsewhere argue are weak Footnote 93 ) procedural mechanisms purported to ensure a degree of parliamentary oversight of the exercise of such powers.

In legislation passed both before and during the pandemic, then, Parliament enacted skeleton legislation giving extremely broad delegated law-making powers to the Government subject to weak statutory limitations, so that the first element of the bargain was undermined.

One might argue that what really matters in this context is not necessarily whether the government could avail of delegated law-making powers under skeleton legislation, but what it did with those powers. In other words, we concede that a public health emergency might be considered one of the (perhaps rare) settings where broad authority is required and appropriate. This is consistent with the nature of the PHA 1984 and CVA 2020 as Acts that were consciously constructed in skeleton form and intended to give the Government all relevant and necessary powers to address a widespread and dangerous public health emergency. The quid pro quo in a healthy constitutional system must, however, be that the gravity of such a delegation of power would be recognised and reflected in Executive self-restraint in its use. As stated above, such self-restraint comprises both technical compliance with the requirement of vires and not stretching the limits of delegated powers by seeking to enact significant policy or address issues only remotely connected to the rationale for delegation through secondary legislation. However, our sample reveals three trends that suggest a failure to exercise self-restraint during the pandemic: increased parliamentary reports of potential ultra vires law-making; policy formation by delegated legislation; and policy laundering.

Throughout the pandemic, concern has been expressed that the Executive did not ensure vires in respect of all regulations. For instance, with respect to sub-delegation of powers, the JCSI has stated that it ‘reported an unusual number of provisions for doubt as to whether they were intra vires’ with respect to the Covid-19 regulations. Footnote 94 Other examples concern regulations that gave the Government powers temporarily to release prisoners under a direction ‘framed by reference to whatever matters the Secretary of State considers appropriate’, Footnote 95 and the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Public Health Information for Passengers Travelling to England) Regulations 2020. Footnote 96 The JCSI's concerns reflected the breadth of the regulations concerning passengers travelling to England, which it considered may have gone beyond the powers given to the Executive in section 45F(2)(a) of the PHA 1984. Footnote 97 Doubts were expressed by the Committee with respect to four further regulations passed within the time period of our analysis, Footnote 98 although these were not debated.

Secondly, delegated legislation has been used during the pandemic for the creation and pursuit of substantial policy. In our sample, we identified eight regulations enacting either a major change to the detail of, or complete change of direction in, the Government's approach to managing the pandemic. Footnote 99 Here we are referring to regulations that introduced a novel nationwide pandemic-response strategy imposing new requirements on the population through a scheme or approach not outlined in primary legislation. A key example of the creation of substantial policy through delegated legislation is provided by regulations introducing and amending local management measures, which became the ‘tier system’. Footnote 100 The tier system determined when and how specific restrictions, many of which implicated human rights, were applied according to Government-defined tiers imposed across different regions in England. The tier level accorded to the severity of restrictions that could be imposed in a particular region, which the Government assigned based on recommendations from scientists and medics taking into account a number of factors including local infection rates and pressure on the NHS.

In debating the initial (ie pre-tier) regulations introducing local restrictions, some Peers expressed dissatisfaction that such extensive and substantive policy measures were being introduced through delegated legislation. For example, Lord Scriven (Liberal Democrats) stated in September 2020 that ‘[n]o longer should Whitehall know best, nor emergency legislation without the proper scrutiny and revision by Parliament be enacted from the tip of a Minister's pen, when there are significant implications for people's freedoms and business survival’. Footnote 101 He further argued that ‘[r]ather than continual emergency legislation on the back of a fag packet, a competent Government would have sat down with the local government and come up with powers and legislation useful…to keep people safe’. Footnote 102 Lord Scriven's statement is exemplary of a significant level of discomfort expressed by some parliamentarians at the scale of the pandemic response being pushed through via delegated rather than primary legislation. Footnote 103

That parliamentarians would have this response to the Government's enacting of a nationwide new strategy for responding to the pandemic via delegated legislation is understandable. Such a strategy does not constitute merely filling in the details of a policy developed by Parliament but is rather a distinct new model of pandemic management that Parliament had no say in moulding due to its inability to amend the secondary legislation. Under this new model, the Government gave itself broad powers to shape and pursue the pandemic response in the sense that it passed powers to impose local restrictions on the basis of criteria mirroring the PHA 1984 (which, as referred to above, required there to be a serious and imminent public health threat requiring such measures to be necessary before these measures could be imposed). Footnote 104 As highlighted by both the Health and Social Care Committee and the Science and Technology Committee, this enabled the Government to impose local restrictions that were not ‘fully clear’ and failed to outline ‘what would be required to exit a particular strategy’. Footnote 105 Transforming the management of the pandemic from the imposition of general restrictions via regulations to the imposition of local restrictions via ministerial direction, where the criteria for such imposition is lacking in clarity, represents a significant gear change in the overall governance of the pandemic. Regulations introducing this new approach thus represent an example of the Government stretching the limits of its delegated powers under the PHA 1984 by using such provisions not merely to impose specific restrictions but to introduce a new system for imposing restrictions that substantially empowered the Government. The argument here falls short of claiming that this new system is ultra vires. Footnote 106 Rather, we take the view that after the initial response, there was room to rethink the government's approach and to craft a legal response to the pandemic in which primary legislation had a more significant role. It is not at all clear why primary legislation could not have been used to introduce the tier system, or at least the core principles and rules of such system. At the time of these regulations the Government was engaged in significant primary law-making in relation to non-urgent non-pandemic-related matters which it could have deprioritised for the purpose of passing pandemic-related primary legislation Footnote 107 further illustrating how, through passing regulations in this way, the Government did not act with the self-restraint needed to maintain the integrity of the constitutional bargain of delegated law-making.

The third feature of the regulations suggesting the Executive did not act with self-restraint is its engagement in ‘policy laundering’ in passing pandemic regulations. Policy laundering is a ‘practice where policy makers make use of other jurisdictions to further their goals’ Footnote 108 and while usually used to describe ‘jurisdiction-hopping’ between national and transnational spaces, also captures neatly the use of one form of authority (in this case authority to make pandemic-related regulations) in pursuit of unrelated goals. Our sample offers two examples of such policy laundering: the Town and Country Planning (Permitted Development and Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 (the TCP Regulations) and the Electric Scooter Trials and Traffic Signs (Coronavirus) Regulations and General Directions 2020 (the EST Regulations). Both regulations, made using negative procedures, have ‘Coronavirus’ in their title, but their connection to the management of and response to the pandemic is far from clear.

The TCP regulations relaxed planning restrictions as part of a post-coronavirus economic renewal package, Footnote 109 but as pointed out in the House of Lords, the connection to the pandemic was tenuous. Lord German (Liberal Democrats) noted that ‘only one’ out of the two regulations in the package was related to the coronavirus Footnote 110 and that the second regulation was ‘both permanent and totally unrelated to the present pandemic’. Why, he wondered, was this change to planning law being ‘misrepresented as a response to the coronavirus health issue’? Footnote 111 Indeed, so strong was the concern that Baroness Wilcox (Liberal Democrats) tabled a motion of regret, although it was eventually not moved. The EST Regulations amended road traffic regulations to allow representative on-road trials of e-scooters to gather evidence on the use and impact of e-scooters, which might also impact on possible future legislation. The SLSC drew these Regulations to the attention of the House of Lords, Footnote 112 while the Department for Transport stated that it considered urgent action was required to provide immediate additional transport capacity, which had been severely restricted by the impact of Covid-19, a justification for which the SLSC stated there was insufficient evidence or consultation. Footnote 113 As noted in the House of Lords, there appeared to be no rational link between the Regulations and the Covid pandemic, and the Regulations related to ‘a major mode of transport development that will affect us all for the long term and way beyond, by comparison, any much shorter-term Covid-19 considerations on addressing transport capacity issues and allowing for social distancing’. Footnote 114 In other words, as Lord German put it, delegated legislation was being used to allow ‘major policy change [to be] side-slipped through Parliament, first, under the cover of a response to the coronavirus crisis and, secondly, by the use of the negative procedure’. Footnote 115

The third and final limb of the constitutional bargain – enabling meaningful parliamentary scrutiny – was also undermined during the pandemic. In the sample that we examined, the Executive consistently elected to use scrutiny-minimising, rather than scrutiny-enabling, mechanisms of making secondary legislation, with 67 out of the 81 statutory instruments we analysed being made using the made affirmative procedure (MAP). The work of the Hansard Society suggests this is representative of the broader practice in pandemic-related delegated law-making. It has found that from the beginning of our timeframe, 9 March 2020, to 26 February 2021, 356 of 415 Covid-19-related statutory instruments had been made using negative procedures. In other words, at least 356 of such regulations entered into force without a draft bring presented in advance to Parliament, and thus without parliamentary scrutiny of their justification, proportionality, and urgency. Footnote 116

Of the 67 regulations in our sample that were made using the MAP, 65 were made using the MAP power set out in section 45R of the PHA 1984. This provides that delegated legislation may be passed under the PHA 1984 using MAP ‘if the instrument contains a declaration that the person making it is of the opinion that, by reason of urgency, it is necessary to make the order without a draft being so laid and approved’. The other regulations in our sample not made using the MAP were instead made using the draft affirmative procedure or Super Affirmative procedure (10) or using the negative procedure and Made Negative procedure and identified by Parliament as needing to be debated by Parliament (3) and not subject to procedure as they were not fully drafted (1). Footnote 117 In the first instance, then, the sample we examined suggests an Executive inclination towards making delegated legislation by means of processes that are designed to maximise Executive room for manoeuvre and minimise parliamentary involvement and which should, ipso facto, be used sparingly. This is not least because – to return to Tucker – they reduce the opportunities for public justification by the Executive either of the content of the regulations or of the claims of urgency that underpin the decision primarily to promulgate them using such processes. Footnote 118 This undermined the extent to which parliament could subject such regulations to meaningful scrutiny.

Notably, such public justification was also undermined by the fact that in relation to all but one set of regulations no impact assessment was provided. Footnote 119 The only impact assessment provided was with respect to the Town and Country Planning (Permitted Development and Miscellaneous Amendments) (England) (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020. This meant that with respect to all other Covid-19 regulations examined in our analysis, the Government provided parliamentarians with no information as to their specific impact on human rights or equalities, even though parliamentarians consistently complained about the absence of such assessments. Footnote 120 Importantly, without such assessments, parliamentarians are stymied in effectively ascertaining the proportionality of such regulations, and therefore assessing their merits in an evidence-based way. This further limited Parliament's ability to engage in meaningful scrutiny of the regulations.

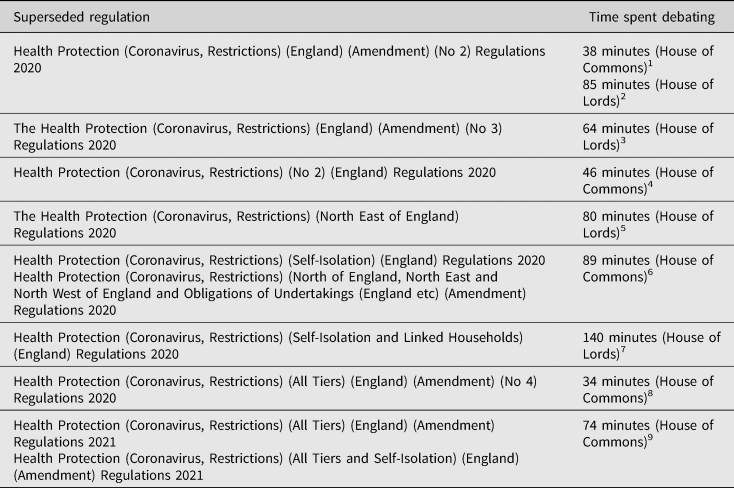

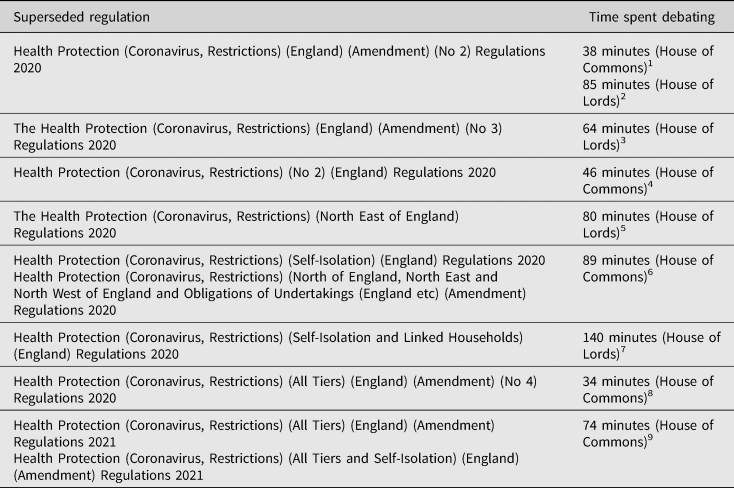

Meaningful scrutiny, in the sense defined by Tucker, was also undermined due to the speed at which regulations were being made, which often rendered the regulations essentially invulnerable to defeat. This is due to the tendency of the Government to schedule debates right at the end of the relevant period allowed for a regulation to be in force before Parliament must consider it (usually 28 sitting days). This tendency meant that in many cases parliamentary scrutiny took place when the relevant regulations had been superseded by new delegated legislation. In our sample, 10 regulations were scrutinised over a total of 9.8 hours of debate after they had already expired or been amended so as to render the debate on such regulations ‘academic’ Footnote 121 and, of course, to remove any opportunity for the regulations to be defeated (Table 1). Instead, these regulations could be introduced, brought into force, and enforced – sometimes with consequences like criminal liability – and then superseded, expired, or revised by new regulations before Parliament ever got to consider them. These 10 regulations included Covid-19 regulations with significant implications for human rights, which – because of both how they were made and the Government's decision to take advantage of the maximum period of time they could operate before being subjected to a parliamentary process – were, in practice, shielded entirely from parliamentary supervision and meaningful scrutiny. This was the subject of repeated protest from both MPs and Lords over the first year of the pandemic. For example, during the debate on the superseded Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) (Amendment) (No 3) Regulations 2020, Lord Scriven (Liberal Democrats) exclaimed that ‘[l]ike lapdogs, we are discussing regulations that we cannot influence, revise or halt. Ministers sit in an office and decide the law, knowing that they are immune from normal parliamentary procedures and cannot be held to account’. Footnote 122 On 8 February 2021, while debating the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (All Tiers) (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2021, Justin Madders MP (Labour) lamented that ‘we are once again retrospectively approving legislation, particularly regulations that have a dramatic impact on individuals’ liberty, as well as an economic impact’. Footnote 123 Such a statement is symbolic of the deep concern regarding the scheduling of the debates on regulations, and the impact such scheduling had on parliamentary scrutiny which was regularly expressed by parliamentarians throughout the year featured in our analysis.

Table 1. Time spent debating superseded regulations

1 5pm–5.38pm, HC DLC, cols 1–14 (10 June 2020).

2 8.21–9.46pm, HL Deb, vol 803, cols 2007–2028 (15 June 2020).

3 1.28pm–2.32pm approximately, HL Deb, vol 804, cols 394–413 (25 June 2020).

4 11.30am–12.16pm, HC DLC, cols 1–16 (16 July 2020).

5 2.55pm–4.20pm approximately, HL Deb, vol 806, cols 886–908 (12 October 2020).

6 4.30pm–5.59pm, HC DLC, cols 1–26 (19 October 2020).

7 2.30pm–4.50pm approximately, HL Deb, vol 809, cols 309–345 (7 January 2021).

8 4.00pm–4.34pm, HC DLC, cols 1–12 (25 June 2021).

9 6.00pm–7.14pm, HC DLC, cols 1–22 (8 February 2021).

In addition to regulations being debated after having been superseded, other regulations were debated after having been in force for a significant period of time. A total of 29 parliamentary debates on the Covid-19 regulations in our sample took place after the regulations had already been in force (in part or in full) for 25 calendar days or more. Importantly, while defeat was a possibility once parliamentary scrutiny was then applied, such a defeat would in practice be of little consequence to the Government considering the pace at which regulations were being passed. Moreover, at this stage, businesses, institutions, and public authorities such as the police were already abiding by and enforcing these regulations, investing where necessary to accommodate them. In other words, the Government effectively developed a practice of continually passing regulations with a view to only keeping them in force until just before the deadline for parliamentary approval and scheduling parliamentary debates right at the end of this time, by which point new regulations would be implemented. Indeed, this is essentially what happened during the period of pandemic delegated law-making we examined. Footnote 124 As a result of the handling of procedural matters surrounding the pandemic delegated legislation in this way, and as set out in the paragraphs above, in many cases Parliament was prevented from exerting meaningful scrutiny of such regulations.

The failures to adhere to the constitutional bargain of delegated law-making during the pandemic that we observe, and which are substantiated by the sample analysis undertaken here, had tangible consequences including, but going beyond, the constitutional damage they may have inflicted. It is appropriate to pause to recall that the harms the constitutional bargain seeks to mitigate can be material as well as institutional. As the Select Committee on the Constitution has noted, the lack of meaningful scrutiny by Parliament created further leeway for the Government to make errors in its regulations, Footnote 125 and many parliamentarians commented on the fact that regulations frequently contained mistakes that were sometimes ‘corrected’ by later regulations. Footnote 126 Moreover, the pace and volume of regulation-making resulted in confusion about what the law required, of whom, when, and in what circumstances, and it was noted that little seemed to be done to support persons with impaired capacity to understand and abide by the regulations. The potential for this was repeatedly cited by the House of Lords. Footnote 127

While pace, volume, incoherence, and poor communication cannot be attributed solely to the reliance on delegated law-making, it seems clear that the effective invulnerability of regulations to defeat and the marginalisation of Parliament as scrutiniser meant that the usual institutional incentives towards coherence and political acceptability may not have operated as keenly in the pandemic as we might ordinarily expect. This clearly contributed to a culture of sub-optimal regulatory quality in a context where people's health and lives were dependent on their impact and effective operation. Footnote 128

Although the prolific use of delegated legislation in the pandemic has attracted significant attention, the analysis that we outline is best understood as illustrating the broad and persistent challenges with delegated law-making that, as discussed above, have long been recognised by Parliament and scholars. Over the course of the pandemic these challenges have crystallised in a context of the general marginalisation of Parliament that both we and others have already remarked upon, Footnote 129 and which is itself an intensification of a longer-standing trend of the Government eroding Parliament's standing within the UK constitution. Footnote 130 During the pandemic the heavy reliance on delegated legislation, brusque and sometimes performative engagement with parliamentary oversight, and simultaneous pursuit of an ambitious legislative agenda and significant constitutional change (most notably relating to Brexit) certainly suggests an Executive determined to prosecute its policy agenda regardless of the strains imposed by and in the Covid-19 pandemic. Combined with the current government's significant parliamentary majority, the acquisition and deployment of significant amounts of discretion Footnote 131 and of relatively unscrutinised power, including delegated legislative power, over the last two years makes visible the degree to which Executive dominance is not only possible but operationalised in Parliament. The breakdown of the constitutional bargain that, at least in principle, underpins delegated law-making during the pandemic is an exposition rather than a source of this dominance and its corrosive effects on core tenets of the UK constitution: parliamentary supremacy and associated accountability to Parliament. Thus, the practice of delegated law-making during the Covid-19 regulations exposes what is a deep constitutional conundrum in the UK.

We note that certain of the dynamics set out above were replicated in comparative Westminster jurisdictions. Footnote 132 For example, in Australia the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Delegated Legislation expressed concerns regarding the use of delegated legislation during the pandemic. Footnote 133 In that jurisdiction, a sizeable proportion of delegated legislation passed during the pandemic was exempt from parliamentary scrutiny, and scrutiny per se was significantly impacted by long-term suspension of the Commonwealth Parliament. Footnote 134 However, these patterns of excessive delegation and limited parliamentary scrutiny were neither inevitable nor universal. New Zealand experienced an early course correction with respect to the use of delegated legislation. In its August 2020 review of delegation, the Regulations Review Committee found that government departments had been ‘receptive’ to feedback expressing concern about the lack of clarity of some Covid-19 regulations, following which the quality of secondary legislation ‘significantly improved’. Footnote 135

This ‘positive influence’ of the Regulations Review Committee is reflective of the New Zealand Government's willingness to engage effectively with Parliament and of the broader constitutionalist mindset that Government exhibited throughout the pandemic. Footnote 136

Indeed, as in New Zealand, delegated law-making in the United Kingdom is not a problem without a solution. As shown in Part 2, seeking to design a mode of balancing the (legitimate) need for delegated law-making with the constitutional imperative for parliamentary supremacy has long been a preoccupation of key actors, including parliamentary committees. Across all three dimensions of the constitutional bargain, changes that would better maintain constitutional equilibrium are possible. Both scholars and parliamentarians have made clear and simple suggestions for reform in the UK context, that may yet serve to mitigate against the problems we have identified. Footnote 137 For example, the DPRRC has proposed avoiding skeleton legislation, except where necessary and fully justified. Footnote 138 The proposal recommends the use of a ‘skeleton bill declaration’ to identify legislation the Government considers to contain skeleton provisions. Footnote 139 Under this scheme, the Executive would be required to make a declaration in an accompanying delegated powers memorandum that a Bill should be understood as creating a skeleton provision, with the DPRRC having a power of scrutiny reserved. When such a declaration is made, the DPRRC and Parliament at large are on notice that what they are being asked to introduce is a skeleton provision and, according to the principle of delimiting delegated power, should proceed with great caution in considering whether this is appropriate, or whether a more limited delegation of law-making power would be preferable. This offers them a prompt to require justification from Government and to subject that justification to robust scrutiny. Footnote 140

Further, simple proposals have been made with a view to compelling executive self-restraint. These include proposals to include sunset clauses in primary legislation to make clear the expectation that the Government will seek to revert to ordinary law-making at the earliest possible opportunity. Footnote 141 This can be achieved not only by ensuring that sunset clauses give rise to expiry/renewal debates in good time (and certainly sooner than two years from the introduction of emergency legislation), but also by treating those sunset debates as situations of meaningful jeopardy for the government. In the pandemic, for example, the CVA 2020 foresaw its expiry two years after its introduction but allowed for both the earlier expiration of particular powers therein (and, indeed, many powers were expired early) and the extension of certain powers beyond the sunset. Footnote 142 However, the broad framework that the CVA 2020 created to govern significant parts of the pandemic response, including the general turn to delegated law-making, was not up for meaningful revision by Parliament within its two-year existence; as we have noted elsewhere, its built-in review mechanisms were ineffective by design. Footnote 143

There are also proposals to empower Parliament to exert proper scrutiny on delegated legislation. This includes a long-standing proposal for a sifting committee with power to determine the level of parliamentary scrutiny particular instruments would receive. Footnote 144 One was established in response to the legislation governing the UK's withdrawal from the European Union. Following the inclusion of exceptionally broad powers to create delegated legislation, including Henry VIII powers, in section 8 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, a new Commons committee, the European Statutory Instruments Committee, was established to examine and report on Government decisions to subject delegated legislation to negative procedures. Footnote 145 The SLSC added a similar function to its remit. Footnote 146 As a result, the SLSC considers the policy effects of statutory instruments and the type of procedure delegated legislation should be subject to. Footnote 147 There is no equivalent body made up of MPs that performs a similar function. Thus, there remains scope to enhance the scrutiny of delegated legislation through the establishment of a body specifically designed for MPs to sift such legislation and determine what kind of procedure they should be subject to.

Even if such a sifting committee were established, however, the likelihood is that in a situation of urgency or exigency – such as that faced in the Covid-19 pandemic – the volume of regulations and pressures of time might mean that scrutiny gaps would appear in any future public health emergency. The question that then arises is whether we really need to continue to do things in the way that we do them now. Even bearing in mind that exact epidemiological and social conditions will vary across public health crises, and that different diseases will have different characteristics and behavioural patterns, the general sense of the kinds of powers that might be needed to safeguard public health can largely be predicted. Indeed, they are predicted in the PHA 1984 as amended which, as already noted, has been the primary source of regulations over the course of the pandemic. We know this not only from local and comparative experience, but also from the international best practice and standards that exist to support states in ensuring preparedness for future emergencies. Footnote 148 Thus, while the exact scale, scope, and perhaps combination of measures that might be considered necessary in each situation may only be determinable within the concrete conditions of a crisis, the nature and possible scales of those interventions can be foreseen and, thus, can be debated in advance. This kind of preparatory practice would not bind the government, which would still have the capacity to adapt to the realities of the situation it sought to address, but it would provide a previously scrutinised set of principles and indication of approach to proportionality, necessity, and appropriateness to guide Ministers and provide Parliament with a jumping-off point for concrete scrutiny. Legislative and regulatory preparedness of this kind would indicate a shift to crisis management in situations of reasonably foreseeable exigency and recognise that scrutiny of crisis responses can have different temporalities to those imposed by the immediacy of an emergency. Footnote 149 Although there were some indications that provisions of the CVA 2020 had been drafted in the context of ‘Exercise Cygnus’, Footnote 150 as the Constitution Committee noted, these were not subject to parliamentary consultation, Footnote 151 thus representing a missed opportunity to enhance the legitimacy of – and potentially improve Parliament's input on – the UK government's response to the emergency.

The obvious contention that improving safeguards and parliamentary accountability in a public emergency context is a matter of political will has been recently confirmed by the enactment by the Scottish Parliament of the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Act 2022. Section 1 of this Act amends the Public Health etc (Scotland) Act 2008, which provides the Scottish legislative framework for the legal response to a public health emergency. Crucially, the amendments introduced a new requirement to trigger emergency law-making powers in the form of a ‘public health declaration’ (new section 86B). These declarations can only be made if ‘an infectious disease or contaminant constitutes or may constitute a danger to human health’ and public health regulations ‘may be a way of protecting against this danger’. This declaration must be laid before Parliament and approved by a motion. There is a duty on ministers to revoke this declaration if the conditions for its making no longer apply, with the effect of ceasing the power to make public health regulations. Other significant amendments are to provide in primary legislation the sort of things that ministers can do in exercising the powers, specific substantive limitations on the emergency law-making powers and review processes. Footnote 152

While there is still room for improving this framework, the Scottish 2022 Act illustrates that another, more accountable, approach to delegation in public health emergencies is possible. It reinforces the impression, gleaned also from the recently suggested reforms considered above, that there is no shortage of proposals to strengthen the constitutional bargain of delegated legislation. What is lacking is the political will to wean governments off the power to make law unscrutinised.